In 1983, at a theatre workshop conducted by NGO Alarippu in Vanvasi Seva Ashram, Mirzapur, a male participant from Rajasthan proudly revealed his wife was revered in his village because she had vowed to commit Sati after his death. Horrified, the women participants decided to stage a play condemning the glorification of Sati. Intezaar, a play written by them, depicted a young girl who had barely spent seven hours with her husband, was urged by the villagers to attain divinity by immolating herself on her dead husband’s pyre. But Chhoti, the wife, wants to live, not worshipped. She courageously walks out of her marital home while her in-laws are asleep — to a new dawn.

Walking Out, Speaking Up: Feminist Street Theatre in India, authored by Deepti Priya Mehrotra, describes many such plays that are part of a genre of theatre that is performed, to raise awareness about women’s issues. But the book does not tell you if Intezaar was staged in Rajasthan where Sati was practised and celebrated. It does, however, state that Intezaar was pulled out of hibernation four years later, when women’s groups launched country-wide campaigns against the much-lauded immolation of Roop Kanwar in 1987, Deorala.

As Mehrotra points out at the start of her book, feminist street theatre came into being in association with the autonomous women’s movement. It was a part of a larger movement that sought to rectify unequal gender equations and bring an end to the atrocities against women, with its most vibrant phase being from the late 1970s to the 1980s.

Across the country, women’s collectives, students, and institutions conducted workshops on feminist street theatre, staged plays with stirring songs, improvised dances and identifiable plots. Often, the actors were victims of domestic abuse, or gender inequality. Encouraged by groups such as Sahiyar Stree Sanghatan, Stree Mukti Sanghatana, Sabla Sangh, to shed their inhibitions, share their unhappy experiences and express their desires, the victims found a cathartic release in portraying scenes from their own lives. The plots of plays weaved-in real-life incidents and kept open endings which viewers could decide. So, the exercise was cathartic — for the performers and the audience.

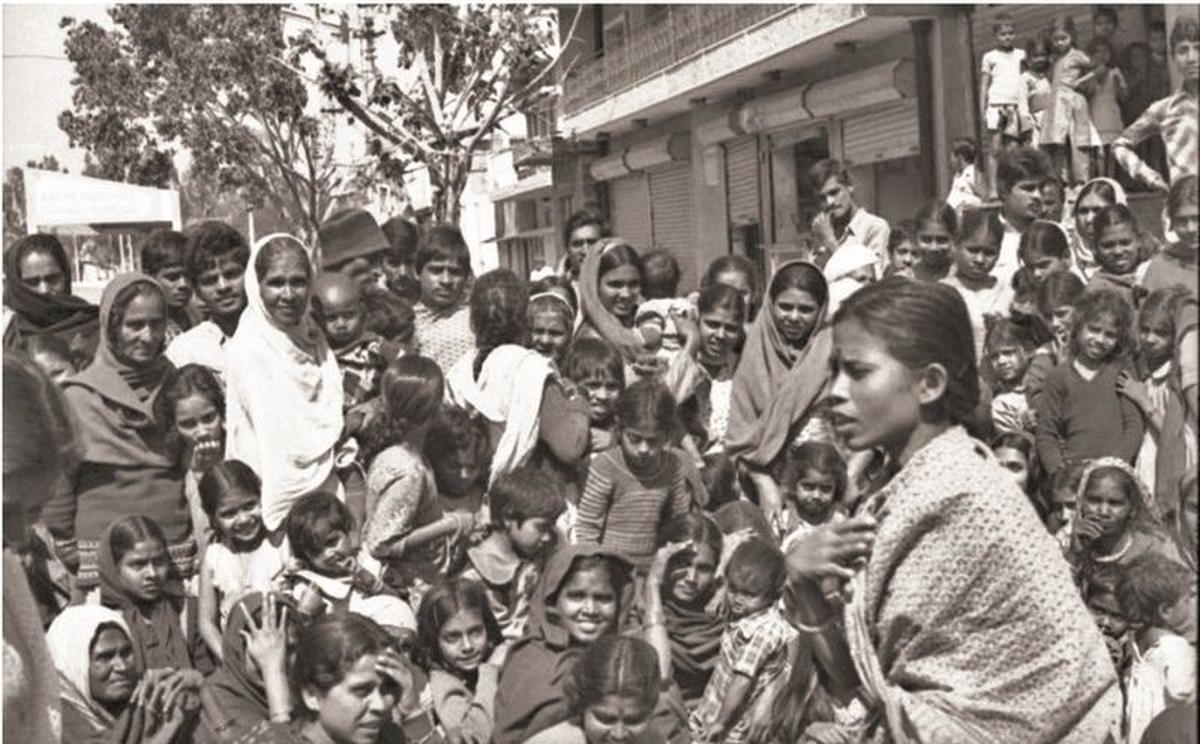

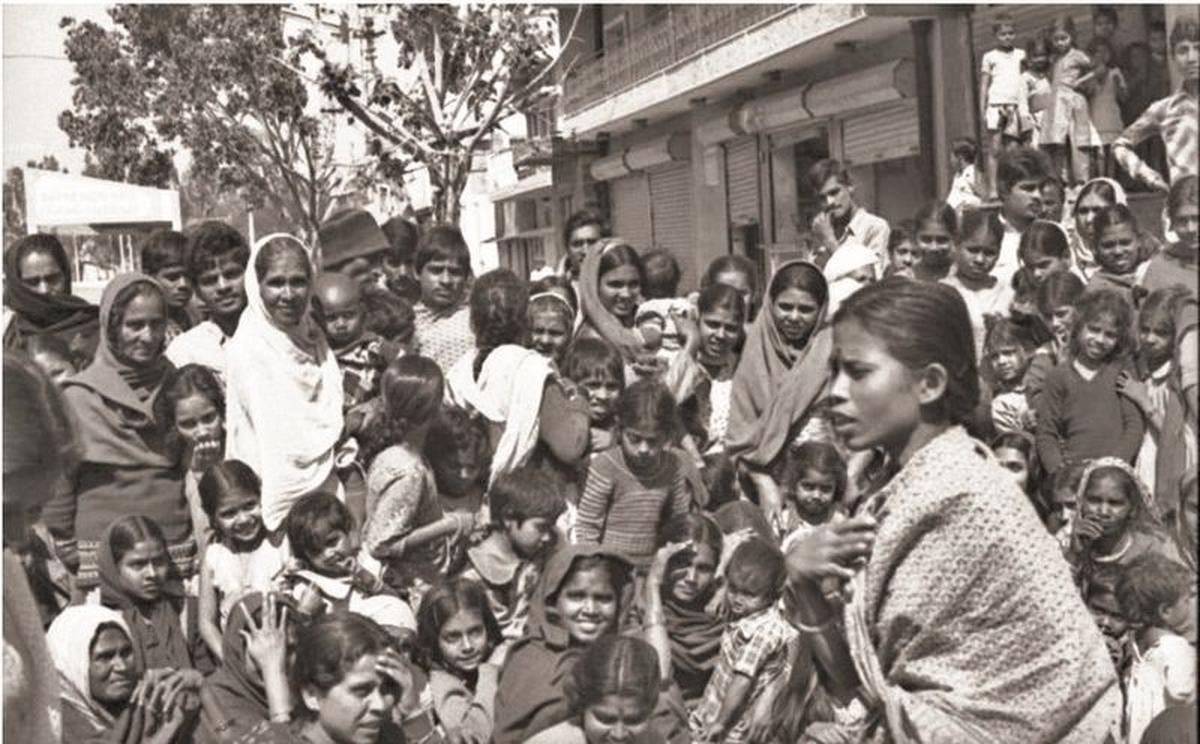

A gathering at a street play in Delhi in the 1980s

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy: Walking Out, Speaking Up

It was from street plays that actresses like Shanti emerged. Shanti grew up earning a living in stone quarries of Rajasthan. After she became a member of Sabla Sangh, she learnt to read and write, produce and write plays. Her talent in folk singing and dancing added to her powerful performances and helped her write entertaining, meaningful plays. She wrote plays such as Mere Dukh Khareedogi for national-level women’s conferences and Suhagan Abhagan in which she used three dolls to depict an unmarried woman, a married woman and a widow and asked participants to describe the dolls as they saw them. Her audience would often have tears pouring down their cheeks sharing their personal stories. Shanti moved audiences— from the crowded bastis of Delhi to the World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995.

When Shahjahan’s daughter died, in 1978, due to domestic violence, Shahjahan joined a shelter home, Shakti Shalini, to support women in crisis. Thereafter, she set up Nav Shrishti, to educate girls of her basti, so they could be self-sufficient and not suffer her daughter’s fate. Within a decade, Nav Shrishti was teaching hundreds of girls, and a few boys as-well, in seven working class areas of Delhi. Then, in 1998, Shahjahan turned to street theatre to educate the community at large on gender and social issues. With help from NGOs — Mehek and Alarippu — Shahjahan’s girls performed in plays such as Main Anpadh Kyun that had a visible impact on the ground, empowering participants and changing the perspective of basti-dwellers.

In effect, Shahjahan tackled women’s issues in a holistic manner. “Naarivaad, narivadi soch is critical for me. There is no limit to this work. If we reach one post there is another ahead,” she explained in a documentary by Vishnu Mathur.

Walking Out, Speaking Up recreates that heady period of feminist street theatre when attempts to unshackle women from patriarchal norms was at its peak in various fields, and stories like Shahjahan’s and Shanti’s are inspiring. Mehrotra’s description of the enthusiasm and dedication of groups across the country, creating immersive, feminist theatre, four decades ago, makes you nostalgic.

However, the book tends to be repetitive and sags in parts because it reads like a thesis.

Also, one fails to understand why Mehrotra left the feminist subject of the significant street theatre group Jan Natya Manch (Janam) out of her ambit. Though she mentions a few of Janam’s plays like Aurat, on the struggles of working class women and Yeh Bhi Hinsa Hai that focused on the violence against women in Hindu mythology, she does not trace their history as she does of the plays of other groups. Mehrotra’s reason for excluding Janam is that it does not identify itself as a feminist group and is not women-predominant. An unconvincing argument because if the above street plays encouraged women to walk out or speak up, then the evolution and impact of these plays should have been discussed.

Published – December 30, 2025 01:11 pm IST