If cinema holds up the mirror to society, what did it tell us about who we have become in 2025? The films that connected most strongly weren’t the best-behaved, or the ones that followed formula or genre conventions, or opened new doors, but the ones willing to let the tone wobble or blow the door open off its hinges. Politically incorrect characters, impulsive and questionable behaviour, and narratives blending facts with fiction, committed more to passion than rules… with CBFC providing the whitewash. People are warming up to the dirty and ugly side of conflicts.

Curated Cool Fail

This was immediately visible against the year’s dominant stylistic impulse: reel-highlight filmmaking. Coolie(dir. Lokesh Kanagaraj) and Thug Life (dir. Mani Ratnam) were technically assured, even muscular, featuring legends Rajinikanth and Kamal Haasan looking their best, packed with whistle-worthy moments. Yet the emphasis on entrances, elevations, punches and punchlines — reel-ready mini-episodes and money shots for trailer — often made them feel curated rather than lived-in, as though each scene was already negotiating its afterlife on social media before the film itself had fully arrived. They banked almost entirely on vibe. The things storytellers do for a whistle!

A still from ‘Coolie’

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

What landed better was Ajith Kumar’s Good Bad Ugly (dir. Adhik Ravichandran), largely because it refused to discipline its own excess, leaning into pulp and exaggeration with enough self-awareness to make looseness feel intentional rather than accidental.

Scripts grew up

The same instinct animated the year’s most engaging young, script-led coming-of-age films. Saiyaara(dir. Mohit Suri), Dude(dir. Keerthiswaran), Bison Kaalamaadan(dir. Mari Selvaraj), Dragon(dir. Ashwath Marimuthu), Aaromaley (dir. Sarang Thiagu), The Girlfriend (dir. Rahul Ravindran) and Bad Girl (dir. Varsha Bharath) allowed their characters to be impulsive, contradictory and occasionally unlikable, resisting the urge to sand down behaviour in the name of relatability. Messiness here wasn’t a flaw to be corrected but the emotional register the films chose to operate in.

Notably, many of these films foregrounded female desire, anger and refusal without packaging them as lessons or redemption arcs. Disorder was not something the women had to grow out of. It was something the films trusted us to sit with.

Franchise Fatigue?

By contrast, franchise films that treated alpha male stars as stabilising devices fell prey to crowd-pleasing tropes and formula have failed. The muted response to War 2 (dir. Ayan Mukerji) and Thammasuggested not a rejection of continuation, but impatience with repetition without reinvention — inherited emotional beats replayed with increasing efficiency and diminishing surprise.

A still from ‘Thamma’

| Photo Credit:

Maddock Films

Indies return home to OTT

Indie cinema once again returned to being discovered on OTT. After Kanu Behl’s Agra sparked a discussion on the quality of screens given to independent films, many films found their audience online. Anurag Kashyap returned to form with his two-part Nishaanchi — Manmohan Desai storytelling filtered through his auteur sensibility. Neeraj Ghaywan’s sensitive portrait of friendship during the pandemic, Homebound, surprised with its humanity and empathy and deservedly became India’s Oscars entry. After being tweaked by the Censors to acknowledge the efforts of governments and COVID warriors, the film finally found its audience on Netflix.

Karan Tejpal’s Stolen was a tense, gripping thriller — a car crash we couldn’t look away from. Anusha Rizvi’s The Great Shamsuddin Family, which premiered on Prime Video, was a lovely ensemble piece — subversive, humane and quietly political — discussing difference with a tameez and empathy that mainstream discourse seems to have forgotten.

Reinventing myths

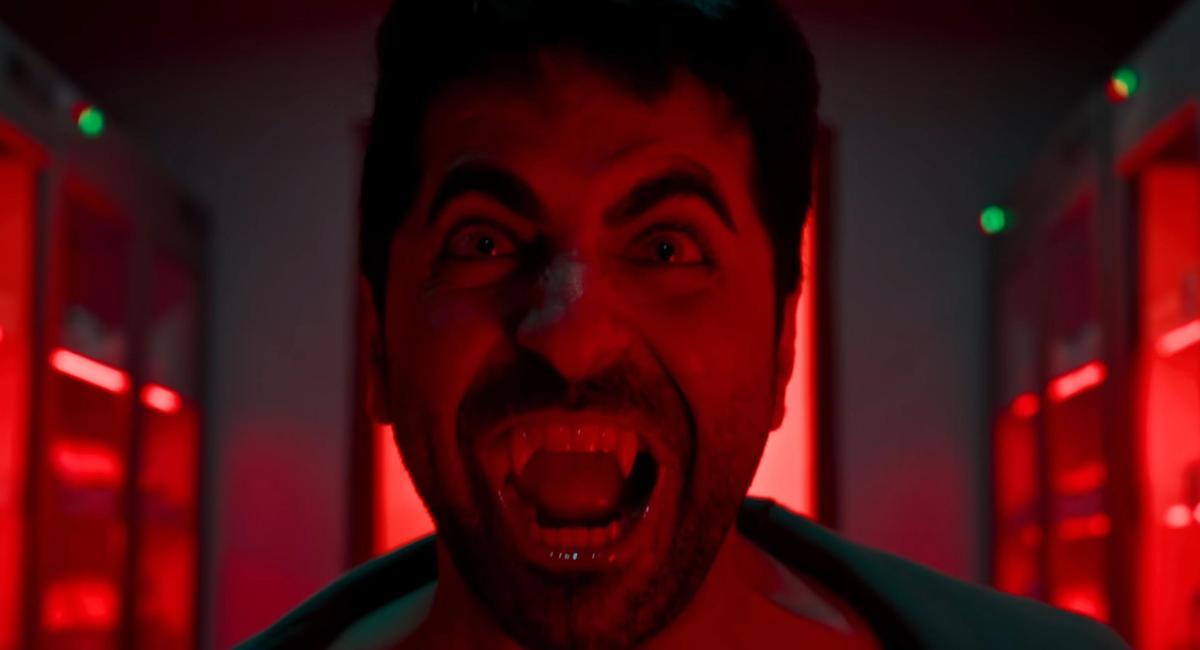

Regional cinema, meanwhile, demonstrated the value of conviction over calibration. Kantara: Chapter 1 (dir. Rishab Shetty) and Lokah: Chapter – 1: Chandra(dir. Dominic Arun) committed fully to their worlds and belief systems, showing little interest in pre-emptively translating themselves for broader consumption. Household myths came to life, enabled by technology and star charisma. The successful ones dove deep into folklore and found thematic modern resonance.

Naslen and Kalyani Priyadarshan in ‘Lokah Chapter 1 : Chandra’.

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Equally brave was Dulquer Salman’s career best Kaantha(dir. Selvamani Selvaraj), where the director makes the audience sound like a bad word.

The mirror talks back

The year’s most revealing moment came when cinema’s ideological positioning collided directly with audience scrutiny. Dhurandhar(dir. Aditya Dhar) reframed terrorism — an India–Pakistan state conflict as a personal Hindu–Muslim issue, replacing geopolitical complexity with ideological bias. What followed proved more instructive than the film itself: viewers interrogated it, debated it and fact-checked it, culminating in Dhruv Rathee’s explainer video Bhawander crossing four crore views across platforms in just two days.

Ranveer Singh in ‘Dhurandhar’

| Photo Credit:

JioStudios

Looking ahead, early 2026 will see Vijay’s Jana Nayagan (dir. H. Vinoth), positioned as both cinematic farewell and political vehicle, arriving alongside Parasakthi— a title that once launched political cinema in Tamil Nadu and, through it, a young screenwriter named M. Karunanidhi.

Cinema, then, does hold up a mirror. Except today, the mirror no longer just reflects; it speaks back. Audiences answer, argue, verify and push conversations beyond the screen — often in directions the films themselves did not intend.

But in 2025, one thing was clear: the conversation is no longer one-way — and we are in the middle of a screaming match with the mirror.

Published – December 26, 2025 04:39 pm IST