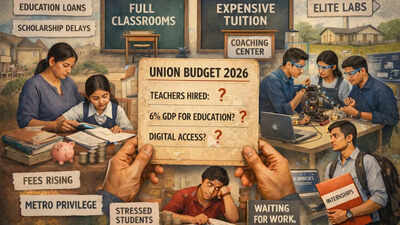

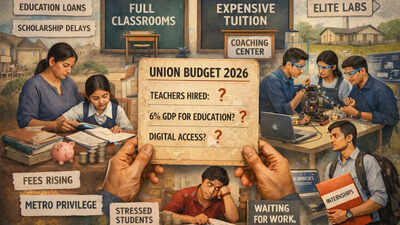

Union Budget 2026 will be read less like a policy document and more like a report card—marked by two examiners who rarely agree but always pay: the parent who funds the journey, and the student who carries its weight. For students, the Budget is not a speech; it is a promise about ordinary days. It is the difference between a classroom where a teacher shows up and one where learning is outsourced to coaching by default; between “digital learning” as a slogan and digital learning as a working device, usable connectivity and a teacher who can actually teach with it. It is also a test of fairness: Whether advanced labs, AI-enabled tools and skill programmes travel beyond elite schools and big-city campuses, or remain another postcode privilege dressed up as reform.Parents will read the same Budget through the household ledger. They will look for affordability signals—scholarships that reach on time, and education loans that feel like mobility rather than a slow-burn trap. They will also look for something that rarely makes it into Budget headlines but dominates student life: well-being. In an education system where stress has become a parallel curriculum, counselling and support are no longer “soft” add-ons; families increasingly treat them as core infrastructure, as essential as classrooms and libraries. Budget 2026, then, will be judged not by the number of schemes it can list, but by whether it makes schooling and college less dependent on private coping mechanisms—and more reliably public, in the way parents have always assumed a republic should be. Here is what students and parents are really looking for this year, mapped to the pressures they live with, not the schemes the government lists.

Funding for learning outcomes, not scheme expansion

Parents do not experience schemes. They experience whether their child can read a paragraph and do basic sums without the family having to pay for tuition. That is why Budget 2026 expectations will lean towards visible foundational gains, not new programme names. The real test is what the money backs inside schools. If the spending is aimed at what happens between the first bell and dispersal, results are easier to feel: More reading and basic maths time in the timetable (not just after-school remedial camps), classroom libraries and graded readers so practice becomes daily, and simple maths kits that help children understand subtraction instead of fearing it. Parents will also look for checks that make sense to them: Short, regular skill tests that show progress, not memory-heavy exams; Teacher support that reaches classrooms, not just one-off training certificates. India’s NIPUN Bharat mission sets the target of foundational literacy and numeracy for every child by 2026–27; Budget 2026 is where that target either gets real backing—or slips quietly into the future.

Teacher recruitment and continuous training as the primary spend

For students, nothing substitutes for a competent teacher who shows up daily. For parents, teacher availability is the hidden determinant of whether coaching becomes “mandatory”. Primary sources already underline the capacity constraint: The government’s UDISE+ release notes that single-teacher schools remain in six figures: 104,125 in 2024–25. At the same time, official scheme frameworks position training as core plumbing: Samagra Shiksha’s implementation framework explicitly provides support for induction and in-service teacher training through SCERTs and related institutions. In Budget 2026, families will look for one clear shift: Make teacher hiring and ongoing training the main spend—not a small add-on.

A credible roadmap towards 6% of GDP for education

This is the promise that returns every few years because it has not yet arrived. NEP 2020 explicitly states that the Centre and States will work to raise public investment in education to 6% of GDP ‘at the earliest’. Families will not parse fiscal federalism, but they will read Budget 2026 for a believable pathway: Timelines, sequencing, and visibility. A Parliament reply of Dec 4, 2024, cites an official estimate that total expenditure on education (Centre + States/UTs) stood at 4.12% of GDP for 2021–22 (based on the government’s “Analysis of Budgeted Expenditure on Education”). The gap is now numerically clear and expectations will follow.

Digital access for all: Devices, connectivity, and teacher readiness

Students hear “digital learning” and think in practical terms: A device, data, and a teacher who knows how to use both. Without all three, “digital” stops being a solution and starts becoming another amplifier of inequality. Last year’s Budget messaging leaned heavily on connectivity, with the stated intent of providing broadband to all government secondary schools under BharatNet within three years. A Lok Sabha reply dated December 3, 2025 reported 67,955 working FTTH connections in government schools under the programme. UDISE+ infrastructure updates suggest movement at the school level too: the share of schools with computer access rose from 57.2% in 2023–24 to 64.7% in 2024–25. Budget 2026 will therefore be judged on whether “digital” means the full stack—devices, reliable connectivity, and teacher readiness—not fibre alone.

AI and advanced labs beyond elite schools and metros

When AI and ‘future skills’ stay locked inside elite campuses, students read the message clearly: this is reform as performance. Families, meanwhile, look for something more basic—proof that advanced learning will travel beyond a handful of metros, especially into government schools where opportunity is meant to be public. The government’s own Budget 2025–26 pitch leaned into innovation, promising 50,000 Atal Tinkering Labs (ATLs) in government schools over five years. But by Budget 2026, the yardstick shifts. Labs cannot remain ribbon-cutting infrastructure—good for photographs, thin on learning. Parents and students will watch for the signals that make these spaces real: Timetabled lab hours, mentor networks that actually show up, consumables and maintenance budgets that don’t run out mid-term, and teachers trained to run hands-on sessions without turning it into an annual “activity”. The point is equity. A student in a district headquarters—or a small town just beyond it—should not be learning the future second-hand while a flagship urban school gets it first.

Skills embedded in timetables and degrees, not add-on certificates

Students are tired of being told to “do a course” after doing a degree. The expectation is institutional embedding: Skills and experiential learning as credit-bearing parts of schooling and higher education. The government has already created the architecture for this: The National Credit Framework (NCrF) is designed as a single meta-framework integrating academics, skilling and experiential learning, operationalised through the Academic Bank of Credits. UGC’s internship guidelines also explicitly allow credit allocation for internships within UG programmes. Budget 2026 expectations will focus on whether this architecture becomes routine practice, not a PDF promise.

A real education-to-jobs bridge via apprenticeships and internships

The moment calls for fewer motivational speeches and more paid, structured exposure to work. The scaffolding, at least on paper, is already in place. UGC’s Apprenticeship Embedded Degree Programme (AEDP) Guidelines 2025 position apprenticeship as the bridge between what students learn in classrooms and what employers actually demand, and require a formal tripartite agreement among the higher-education institution, the employer and the student. On the skilling side, the National Apprenticeship Promotion Scheme (NAPS) spells out government support, including stipend-sharing up to a notified cap.So Budget 2026 will be read with a very practical question in mind: Does this remain a framework for the well-connected, or does it become a pathway at scale? Students and parents will look for signs of reach—more apprenticeship seats, clearer incentives for employers, predictable stipend flows, and access that is not limited to a few sectors, cities or ‘top’ colleges. In short, not another employability slogan, but a pipeline that an ordinary student can actually enter.

Education affordability: Scholarships and safer student loans

For parents, affordability is not a debate; it is a monthly calculation. In Budget 2026, families will look for signs that the cost of studying is not being quietly transferred to households—through higher out-of-pocket expenses, coaching dependence, or debt. That is why scholarships remain a frontline expectation: Not just more schemes on paper, but clearer targeting and predictable, on-time disbursals. Student loans sit in the same frame. Under the Centre’s CSIS interest-subsidy scheme, eligible borrowers receive an interest subsidy during the moratorium period—the years a student is studying and not earning yet. For students, that moratorium is not a technical term; it is the difference between graduating with breathing room or graduating with an EMI already waiting. In Budget 2026, families will therefore expect affordability support that is simple to access, clearly communicated, and dependable.

Student well-being as core infrastructure

Students rarely ask for “mental health policy”. They ask for something simpler: one adult in the system who takes them seriously before a spiral becomes a headline. Parents, too, are increasingly treating well-being as a school or college capability—not a burden families must manage alone. The Ministry of Education’s MANODARPAN is an official platform for psychosocial support for students, positioned as support “during COVID and beyond”. NCERT similarly describes it as a platform through which students can seek psychosocial support from mental-health experts and counsellors. Budget 2026 expectations, therefore, will centre on whether counselling moves from being a helpline-style safety net to a real institutional layer—trained counsellors on campus, clear referral pathways, and sustained support, not just crisis-time advice.

Delivery or another draft?

Union Budget 2026 will not be remembered for the poetry of its speech, but for the physics of its delivery: What it funds, what it repeats, and what it quietly leaves to households to ‘manage’. That is the lived economics of education in India—where the state’s intentions are often noble, but the family’s coping mechanisms are better organised. When public spending under-feeds learning outcomes, parents do not convene roundtables on pedagogy, they simply pay for tuition. When teachers are too few, or too unsupported, coaching does not remain a choice in the market, it becomes the market. When ‘digital’ means fibre without devices, or devices without teacher readiness, technology stops being reform and starts behaving like a sorting machine dividing those who can convert connectivity into learning from those who can only watch the buffering wheel.The same pattern repeats wherever the system slips. Labs and AI programmes stay clustered in a few postcodes and call it ‘future-ready’. Outside those postcodes, the future arrives as hearsay. Skills are announced like banners, then sold back to students as certificates. Work exposure is promised, but often delivered through networks—an internship for the connected, a webinar for the rest. In the gap between policy and practice, a parallel education economy grows: Coaching centres, crash courses, paid projects, private counselling—each one a private invoice for a public shortfall.What families carry into Budget 2026, then, is not a wish-list. It is an impatience, sharpened by experience. They want affordability with dignity: Scholarships that arrive on time, loans that do not quietly harden into lifelong anxiety, and counselling that exists inside institutions. What remains to be seen is whether the system will behave less like a trial subscription—free until the fine print—and more like a public guarantee.