At the seminal 150th Harivallabh Sangeet Sammelan — 2025 in Jalandhar an elderly bearded man, his turban tied carelessly, a blanket wrapped around to keep away the bitter winter cold, leaned against a pillar, close to the standing heater. “Which concert did you enjoy the most?” I asked. Holding the hand of the little child accompanying him, he said: “It’s not about enjoying the music, it’s my duty. I was brought here as a child by my grandfather, who told me it is Jalandhar’s honour to host this sammelan. I come every year to mark my presence. I used to come with my sons, but now I am here with my grandson.”

This seems to be the reason why Harivallabh, the oldest Hindustani music festival in the country, remains a vibrant centre of music even today. For many artistes and listeners, it is almost like an annual musical pilgrimage.

Shri Devi Talab Mandir in Jalandhar, the venue of the festival.

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

There is always a festive air, and a buzz even at 11p.m., when temperatures can dip to 2 degrees C. Originally called ‘Harballabh’, it used to be held at the Tripuramalini Devi temple, one of the 51 ‘Shakti peeths’. Called Devi Talao (talao means pond), the area was outside Jalandhar city, and an ascetic, Baba Hariballabh, who lived there loved music. Around the same time, in Bikrampura in Jalandhar, music soirees used to be held in Bikrama Hall, the haveli of Kapurthala royal Bikrama Singh. ‘Beenkaar’ (rudra veena player) Mir Nasir Ahmed, who had fled the Mughal court of Bahadur Shah Zafar during the 1857 mutiny, was under his patronage. Musicians, including Baba Hariballabh, would come to meet Mir, who was a descendant of Tansen.

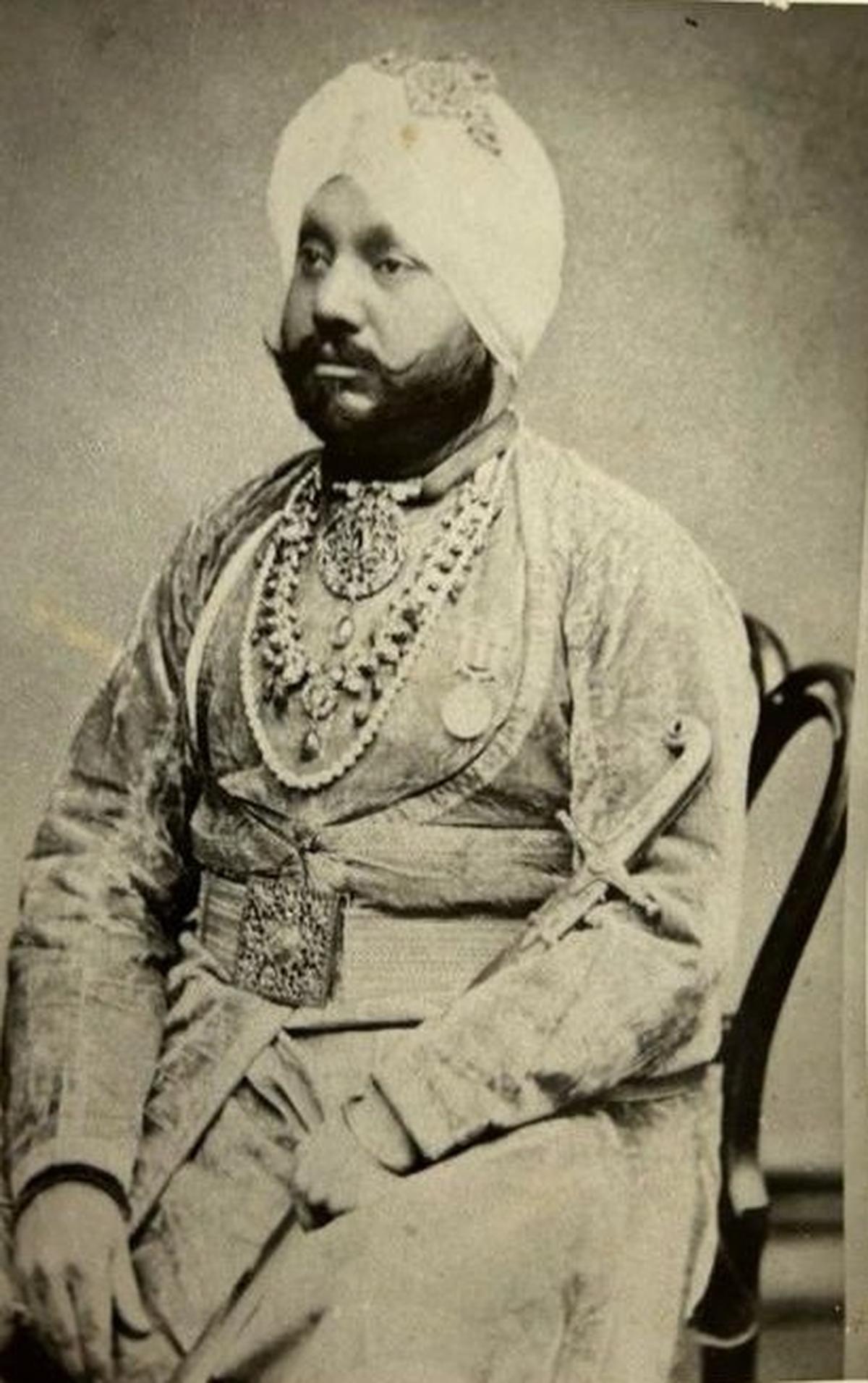

Kapurthala royal Bikrama Singh gave land near the Tripuramalini Devi temple for the festival

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

When Hariballabh passed away in 1875, his disciples wanted to hold an annual music ‘haazri’ in his memory, and Bikrama Singh gave them land near the temple. Mir urged musicians to perform there, and it was considered an honour to get that opportunity. If a musician could appeal to the Hariballabh audience, he was acknowledged as good. Musicians would arrive at Jalandhar in the last week of December, and wait for an opportunity to perform at the week-long, all-day fest. Till then, they would stay with music lovers in the town. Did you know that when the legendary Bhimsen Joshi was in search of a guru, he came to Hariballabh?

Harivallabh Sangeet Sammelan president Poornima Beri says the audience has grown organically. “I remember coming as a bride to the festival, some 60 years ago, listening and absorbing. That’s how it’s been for most of the audience here.”

Begum Parveen Sultana remembers singing at Hariballabh in 1969, when she was still in her teens. “There were thousands of people listening,” she recalls. People used to sit on straw covered with cloth spread on the cold ground, huddled inside the blankets they carried.

Dhrupad exponent Ustad Wasifuddin Dagar performing at the festival

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

With the passage of time, the funds needed to hold the festival increased, and prominent families in the area chipped in. Artistes started to be paid nominal fees. But, sometime in the 1960s, other festivals gained visibility, and Jalandhar’s aura started fading. The ad hoc arrangements, which used to be viewed indulgently by artistes as being part of the quaint charm of the festival, started to irk. And then, Ashwini Kumar, a senior police officer posted in Jalandhar, took charge of the festival, formulated a trust and things began looking up.

His wife Renu, who has fond memories of the festival, says,“Artistes we invited have become friends over the years.”

The Harivallabh Trust also started music contests for young aspirants. Students from colleges outside Jalandhar attend these, and there is a serious attempt to take the music to the younger generation.

The festival has thrived despite struggles. There was a period of lull after Ashwini Kumar’s time, and in the 1990s, Poornima Beri, a music lover, was chosen to lead the committee. “We have had unanimous decisions most of the time, but it’s not been easy — we have controlled our egos. Each of us has put in our money into the festival at some stage.”

Sitar exponent Ustad Shujaat Khan has fond memories of performing and interacting with artistes at the festival

| Photo Credit:

R. Ravindran

Some of the artistes who have performed here like to hold on to their memories of a festival driven by passion for music. Ustad Shujaat Khan says it was once considered the premier festival of the world. “There was a Hotel Skylark. All of us lived there during the fest, laughed, and had a great time.”

Over the years, the festival has also faced criticism for ignoring Punjabi artistes at the cost of giving opportunities to gharana exponents. But, all of this is forgotten on the last day of the festival. The concluding concert is usually held at 4 a.m., when everyone is enveloped by the warmth of the music. It has been a visual delight for a century-and-a-half — as part of an old tradition, at the close of the music, the stage is showered with flowers.

Published – January 23, 2026 06:35 pm IST