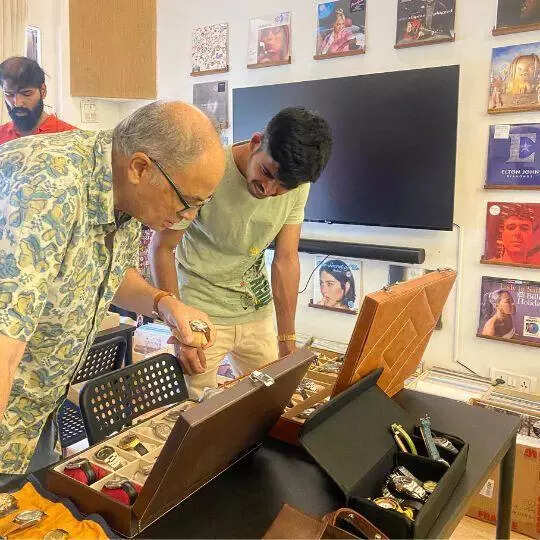

For 13 years, Varun Jashnani searched for a person he knew nothing about, save their name, ‘N Bhowmick’, engraved on the steel caseback of a pre-1930s Favre Leuba Sea-Chief. Once owned by the unknown ‘N’, the watch travelled through the backchannels of the pre-owned vintage watch market, from Thrissur to a small Byculla watch shop, where Jashnani, then 24 and younger than the average age of a vintage watch, snapped it up.A vintage watch—typically defined as being at least 25 years old—holds multiple stories: of its provenance, accidents, brand history, craft and technology, servicing journey, and, finally, how it came to rest on a wrist. Keen to learn and tell these stories, a growing community of watch enthusiasts is gathering around the fading lume of vintage timepieces, their ears pressed close to the weathered dials.Jashnani, Vice-President at the real estate firm Lighthouse Luxury, is an avid listener, drawn to mechanical movements that come to life when wound. “I was hooked by the look and feel of this mechanical piece,” he says of a first-generation HMT Kohinoor he spotted in 2011 in the display case of his watch-repair chacha in Byculla. “It stood out from the quartz watches in the market. Here was a watch you could engage with. And it only cost Rs 2,000.” Hooked, he began researching and collecting mechanical wristwatches; today, they make up a large part of his 110-piece collection, 105 of which are vintage.Vintage watches are conversation starters, says Jude de Souza, founder of The Revolver Club (TRC), an artisanal music store that branched into watches 3 years ago. “In a world where people spend hideous amounts of money on blah watches, these stand out. They speak to a time when companies were allowed to take risks, and individuality was valued over scale and the bottom line,” he says, recalling the pre-quartz era (70s–80s).Seiko launched the first quartz wristwatch, the Astron 35SQ, in 1969. By the late 80s, what many call the Quartz Crisis forced nearly 1,000 Swiss watchmakers out of business, with overall production falling to nearly a third. This made surviving mechanical and automatic pieces rarer, more valuable, and highly coveted.Vintage watch enthusiasts scour the market for these models, often willing to shoulder the cost of restoration. “The condition of the watch, its design and rarity are what typically draws us to a timepiece,” says Jashnani. “Budget, naturally, narrows down the search.”As interest in vintage watches grows, supply channels are starting to widen.TRC started sourcing pieces from their existing customer base, and from a handful of trusted dealers and service centres. But as word spread, sellers reached out to them from across the country, contributing to their catalogue with the familiar (HMT, Citizen, Seiko), the foreign (Jemis, Titoni, Nino, and the USSR-era Raketa and Zaria), and the premium (Omega, Cartier, Favre Leuba, Tissot and Rolex).Keen to build “an ecosystem” around vintage watches, they organise watch meets, where people drop by to talk watches and browse pieces on display, which include ones loaned from personal collections. They even trade models between them. “Initially, our product drops focused only on old-school HMTs, priced between Rs 1,500–2,000.” Around 40 to 50 pieces would sell out in 2 days.“We want to de-intimidate the average young person who wants to get into watches by showing them that there are tons of Seikos, HMTs and Citizens that are affordable and have their own unique value. You don’t need to buy an Omega or a Rolex to be a watch guy,” de Souza maintains. Buyers fall into 2 camps: under-25s buying watches under Rs 10,000, and those over 35 spending upwards of Rs 1–2 lakh. Men outnumber women 4 to 1.Many first-time collectors hoping to eventually enter the luxury segment also take the vintage route. “Vintage watches are often considered entry points to luxury watches—you can buy a nice vintage Omega from the 70s at the price of a new Tissot,” says Punit Mehta, Chapter Lead at RedBar India, a watch community that began with 7 enthusiasts during COVID and today counts over 500 members.At a typical RedBar India meet, watches are laid out on a table, with people sitting around them, eating, drinking and admiring the exhibits. Marquee events cover talks by watchmakers, visits to premium service centres, strap-making workshops and luxury brand outings.India’s interest in vintage watches is relatively recent, Mehta notes. “Until the 90s, Italian watch dealers were known to import vintage watches from India, because we didn’t much care for them, while Italians did.” Today, India’s vintage watches are circulating within the country, because demand is rising here, driven by higher disposable incomes, social media, pop and hip-hop culture, and the desire to stand out.On the supply side, a range of online and offline avenues operates across a sliding scale of credibility and trust—from eBay and Facebook Marketplace to specialised platforms like Chrono24, certified pre-owned programmes of major luxury brands and auction houses.“What was once a niche interest limited to a small group of collectors evolved into a more structured and visible segment, marked by higher auction participation, stronger price benchmarks and a growing base of first-time buyers . . . who value vintage watches for their design, engineering and heritage, not just status,” says Hinesh Kotecha, Director of the luxury watch portfolio at AstaGuru Auction House. “While it is difficult to assign an exact value to the Indian vintage wristwatch market, much of which still operates through private sales, it grew steadily over the past decade.“As the market formalises, both buyers and sellers are increasingly turning to service centres to get watches—especially high-value pieces—authenticated, serviced and repaired. “In India, many vintage watches are what collectors call ‘Franken’ or ‘Bombay watches’, meaning they’re not entirely authentic under the hood—the dial may be repainted, movements changed, or parts cannibalised,” says de Souza.Skilled technicians can set things right. Service centres such as My Watch Merchant (MWM) in Goregaon and Pogu Watch Service in Parel started off as neighbourhood repair shops, but as the market expanded, so did their operations. Today, they run sleek labs in multi-storey buildings, employing 7 to 8 technicians.“Finding original parts is the most challenging bit,” admits Paresh Parihar, Director at MWM. “We fabricate parts that are unavailable when the model is no longer manufactured and reliable substitutes cannot be found.” They also tailor watches to individual preferences. “We can make a classy watch look sporty by simply changing the straps.” Ultimately, watches are meant to be worn, not salted away. “The more often you wear them, the longer they’ll last,” he says—advice that runs counter to a familiar Indian instinct to save cherished possessions for special occasions.Another counterintuitive piece of advice is to allow a vintage watch to look vintage. Some clients want them to look as good as new, says Chandraprakash Pogu, founder of Pogu Watch Service, who advises clients to retain the patina because they are signs of a life lived. “Earlier, people didn’t know how to maintain their watches or that they needed to service them regularly, but they are more aware today.” Part of it has to do with pride of ownership, and part, asset appreciation—knowing that a well-kept watch will command a higher value in time.For William Charles, it is both. Charles was 12 when he accidentally broke his father’s cherished Breitling AVI 765, a chronograph he used to time his friends racing. “He was livid,” Charles recalls. Unable to find trusted technicians in Nagpur and unwilling to send the watch to the metros for repair, his father stored the 1950s timepiece in a vintage Japanese hard-candy box. It lay forgotten there until it was disinterred 35 years later, last April, when Charles decided to sell it.“I thought it wouldn’t be worth more than Rs 2 lakh,” says the corporate communications professional. A dealer he found through a newspaper classified quoted Rs 90,000; a second opinion valued it at Rs 8–10 lakh, Charles chuckles. With the original bill and box, which he didn’t have, it could have fetched Rs 12–15 lakh. He spent Rs 88,000 on repairs and servicing, initially intending to sell. But when My Watch Merchant returned the piece to him in September, he couldn’t let it go.“I can’t bring myself to wear it outside; my wrist feels heavy. I never wore a watch worth more than Rs 20,000,” he admits.But he knows the watch must be used if it is to be maintained. So, once in a while, for a couple of hours, he takes it out of the cupboard and wears it at home.Look out for the following events next week:India Watch Weekend 2026 January 17–18 Four Seasons Hotel Tickets on BookMyShowThe Revolver Club Community Meet January 17, 12 pm onwards The Revolver Club, LJ Rd, Mahim Free entryAstaGuru’s ‘Legacy Jewellery, Silver & Timepieces’ auction January 15–16 Astaguru.com